Megaloptera, Trichoptera, Plecoptera… unless you’re a fly fisher, ecologist, or student who has taken part in our stream field experience, these words may sound like a foreign language.

In fact, these are the Greek-based scientific names given to groups of aquatic macroinvertebrates. And if that made things even more confusing, aquatic macroinvertebrates are small, but visible to the naked eye (macro) insects, crustaceans, and mollusks (invertebrates – animals without backbones) that inhabit aquatic environments. These small animals are essential for cycling nutrients through the ecosystem. They feed on smaller zooplankton, filter suspended solids in the water column, scrape algaes and biofilms, shred leaves and other organic matter and then become food for larger animals such as fish, birds and mammals.

Most of the time, they live their lives invisible to us. However, if you’ve ever admired the agility of dragonflies zipping through the air, you’ve encountered the adult life stage of an insect that begins its life underwater, sometimes developing for multiple years before emerging as an adult. Larval/nymph (juvenile) dragonflies are stout, lacking the elongated abdomen of their adult counterparts. Like adult dragonflies, larvae/nymphs are voracious predators, often lying in wait and shooting out their alien-like mouthparts to capture other invertebrates and even small fish!

Likewise, if you’ve ever been annoyed by swarms of midges or mayflies, you’re familiar with another adult life stage of an aquatic macroinvertebrate. Though these swarms may be mildly annoying, they increase the probability of finding a mate and avoiding predation during these insects’ tragically short adult life spans. Some species of mayflies live less than 24 hours and have such short adult lives that they lack functional mouthparts!

If you’re like me, you may have gone through much of life without giving much thought to these underwater residents. So why would anyone care about them? Turns out that different groups of aquatic macroinvertebrates have different tolerances to water conditions, including pollution, sediment, temperature and oxygen levels. Sampling the biological community can tell us a lot about the health of a particular water body, and sampling multiple locations and habitats can give a more comprehensive overview.

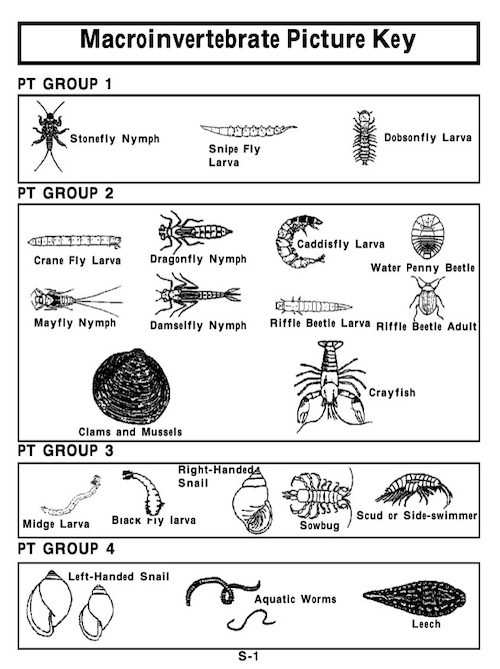

For example, some snails, leeches, aquatic worms, midges, and scuds are organisms that belong to PT (pollution tolerance) Groups 3 and 4 and are tolerant of degraded water conditions. Taking a sample in an impoundment above a dam where water flow slows and sediments stay suspended in the water column where they absorb sunlight thereby increasing the water temperature and decreasing dissolved oxygen, might yield a community composed heavily of organisms from PT Groups 3 and 4. However, sampling downstream where water flows freely, depositing sediments and tumbling over rocks, we might find a more diverse assemblage of organisms, including those that need cooler, clearer water with higher oxygen levels such as those in PT Groups 1 and 2. An important point to keep in mind though, is that finding a diversity of organisms across tolerance groups is more important than finding just a couple of organisms from Groups 1 and 2. Diverse ecosystems have organisms filling different niches which helps maintain stability and resilience when faced with external pressures.

Even if you never encounter these underwater residents, knowing of their existence can hopefully provide a deeper appreciation of the vast life that the Fox River and other aquatic environments support. Students who take part in our field experiences get first hand experience sampling and assessing their local streams, coming away with a greater understanding of daily actions that impact our aquatic inhabitants. We know these students will grow into decision makers and professionals shaping the future of the Fox River Watershed. Knowing these communities of organisms can be affected by dams, excess sediments from construction sites, road salts, pesticides, and fertilizers that find their way into the river can help inform personal decisions, business practices, and local policies. This is one way Friends of the Fox River is working to create a watershed community of caretakers.

If you are intrigued by these marvelous macroinvertebrates, stay tuned for a deeper dive into the world of aquatic macroinvertebrates in future Watershed Weekly articles and the possibility to participate in community sampling events.