By Gary Mechanic, Executive Director

Late last year one of the final pages of a decades long battle to save Long Lake (in Lake County Illinois) came to a close when Illinois’ Attorney General Lisa Madigan announced a settlement with Baxter Healthcare that will end that company’s decades-long pollution of Long Lake. Behind the Attorney General’s suit against a 17 billion dollar multinational corporation, that’s based in Illinois, stands Paige Fitton, Paige’s childhood friend Jennifer, Paige’s mom and dad, and Paige’s grandfather and great-grandfather! It took generations of lake lovers, homeowners and Paige’s family working together for decades to reverse decades of degradation and win a complicated war against a powerful polluter.

This is the first of a three-part series describing that decades long, multi-generational, battle to save Long Lake from a long, slow death by pollution.

Part One – Origin Stories

When the face of the last glacier was retreating to the north about 12,000 years ago, it left behind a lumpy landscape that began draining into the new Fox River. It left ridges (east of Rt. 25 & west of Rt. 31) and hills (like Campton’s) that we pass over today. And it left gigantic blocks of its crumbling ice behind. For some reason a great many of those landlocked “icebergs” were left in the area from Algonquin north into southeastern Wisconsin. As these township-sized blocks compressed the land beneath them, and then melted, they filled this landscape with shallow, water-filled depressions known as kettles, bogs, and pothole lakes.

For thousands of years after the glacier melted away, the wetlands and lakes of the upper Fox River watershed attracted, and supported a huge variety of insects, reptiles, amphibians, fish, birds and mammals. These watering holes also sustained huge migrating populations of birds and large mammals that depended on them as they passed back and forth between their summer and winter homes.

The water in these glacial lakes was clean, clear, and sustained more numbers and kinds of fish than anyone today can imagine. And for thousands of years, the fish, the birds, and the fur-bearing animals that this rich ecosystem supported, also supported a local, and transient, population of countless humans.

Then, the first humans from other ecosystems, on other continents, entered and settled the eastern part of this region. When their numbers grew enough to warrant it, they began drawing straight lines across this glacial landscape to define their new county. T o advertise these distinguishing, and more importantly attractive glacial features, they named their new county “Lake”.

o advertise these distinguishing, and more importantly attractive glacial features, they named their new county “Lake”.

Hot Times, Summer in the City!

For the new settlers these wetlands were not well suited to the kinds of farming they knew and practiced. So the land around these lakes, with their large marshy borders, were not populated or developed as quickly as the better drained prairies to the south and west.

After the Civil War the population of the great city that was developing 50 miles south began edging toward a million. When the heat of summer drove everyone outdoors into the dust, smoke, garbage, smells and diseases of the booming city, it drove those with the wherewithal to escape. Summer cottages became the rage. And a summer cottage on a lake, well that was the next best thing to air-conditioning!

Long Lake

Stephen A. Forbes was State Entomologist of Illinois and Professor of Zoology and Entomology at Illinois State University. He would later become the first Director of the Illinois Natural History Survey. In 1887 he wrote the following in his short report: “The Lake as a Microcosm:”

Stephen A. Forbes was State Entomologist of Illinois and Professor of Zoology and Entomology at Illinois State University. He would later become the first Director of the Illinois Natural History Survey. In 1887 he wrote the following in his short report: “The Lake as a Microcosm:”

“When one sees acres of the shallower water black with water-fowl, and so clogged with weeds that a boat can scarcely be pushed through the mass; when, lifting a handful of the latter he finds them covered with shells and alive with small crustaceans; and then, dragging a towing net for a few minutes, finds it lined with myriads of diatoms and other microscopic Algae, and with multitudes of Entomostraca, he is likely to infer that these waters are everywhere swarming with life, from top to bottom, and from shore to shore.”(Forbes, S.A. 1887. “The Lake as a Microcosm”. Bulletin of the Scientific Association of Peoria, Illinois, pp 77–87. Reprinted in Illinois Natural History Survey Bulletin 15 (9):537–550.)

After extensively surveying several Illinois lakes in the Fox River watershed, he described Long Lake:

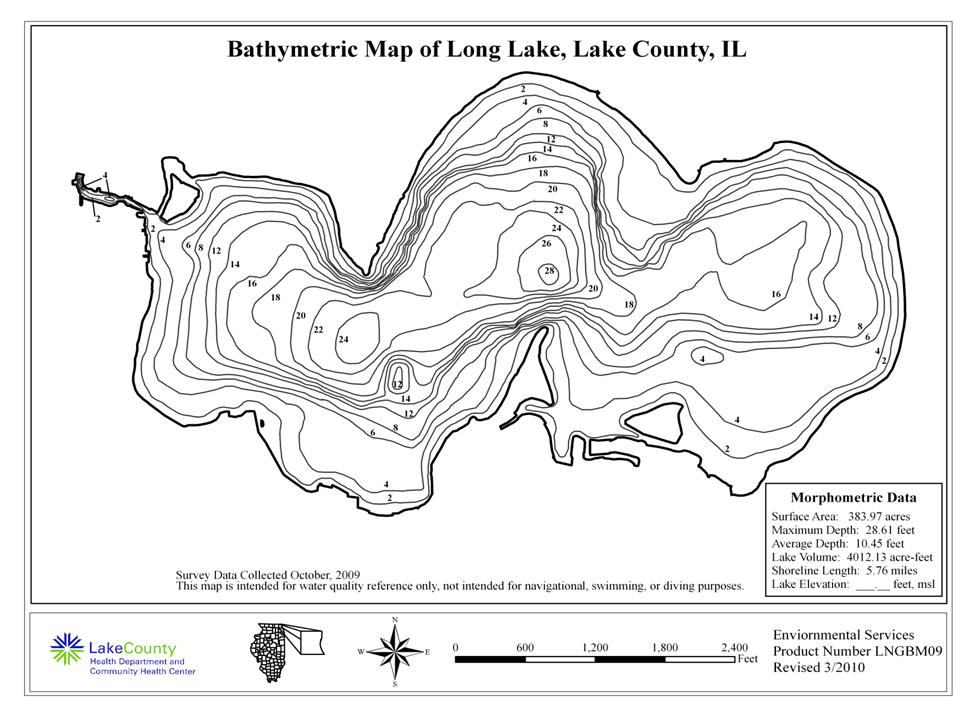

“Long Lake…is about a mile and a half in length by half a mile in breadth. Its banks are all bold except at the western end, where a marshy valley traversed by a small creek, connects it with Fox Lake, at a distance of about two miles. The deepest sounding made was six and a half fathoms, while the average depth of the deepest part of the bed was about five fathoms.”

In C.F. Johnson’s 1896 book “Angling in the Lakes of Northern Illinois: How and Where To Fish Them” (The American Field Publishing Company, Chicago, IL), Long Lake is described as an excellent fishing lake, with extensive aquatic plant beds. According to Johnson “it is no unusual thing for an angler to catch a string of a dozen fine bass weighing from two to four pounds each”.

The abundant fish, clean water, clean air, combined with the relatively inexpensive land so far from the city, became as attractive for the newly arrived humans as they’d been to the birds, beaver, and fox that had lived there for centuries.

Moving On Up: James W. Cooper

In 1874 James Cooper was born the son of a coal miner in Scotland. Like thousands of other Scots, he left his country in 1890 and started a new life in America. He settled in Chicago and began selling iron products for another Scottish immigrant who owned the Gates Iron Works. Gates Iron built the first steam-operated sawmill in the country, at a time when Chicago was the country’s leading producer of milled lumber.

James switched from being an iron merchant to a career in newspaper advertising. By 1906 he was wealthy enough to buy a lot on Long  Lake with his new wife Helen. A couple years later they ordered a cottage from a catalog and had the packages of lumber and nails shipped by rail to the nearby Round Lake depot. It was one of the first cottages built in their small lakeside community on the shore of Long Lake. The next year their first son, James F. Cooper was born.

Lake with his new wife Helen. A couple years later they ordered a cottage from a catalog and had the packages of lumber and nails shipped by rail to the nearby Round Lake depot. It was one of the first cottages built in their small lakeside community on the shore of Long Lake. The next year their first son, James F. Cooper was born.

As the summer population around the lake grew over the next few years, it also grew a population of outhouses and crude septic fields. Many lake users realized that some health rules and lake maintenance would be necessary if they wanted their lake to keep supplying them with a safe place to swim, and fish that were safe to eat.

In 1910 Teddy Roosevelt was getting ready to run again for President, the conservation movement was in its infancy, and James W. Cooper, along with some of his fellow lake neighbors, founded the Long Lake Improvement and Sanitation Association. Today the Association is 109 years old and still going strong.