By Jack Frost MacRae

They were the perfect American tree. They were among the tallest, the widest, and had the straightest grain. They grew fast, were numerous, and were resistant to rot and decay. Their nuts fed billions. They were pretty. And, Mel Torme wrote a celebrated song about them. Then the blight came and the mighty American chestnut vanished.

How poignant that by the time the time Nat King Cole had recorded the 6 immortal words in 1946, there weren’t any chestnuts left to roast.

Importing Invaders

The fungus responsible for the American chestnut blight probably originated from Asian chestnut trees imported in the late 19th century. The specifics of early  importations of Japanese chestnuts are well documented; the earliest may have been in 1876 by nurseryman S. B. Parsons of Flushing, New York. But, there were so many records of these trees being imported and shipped through mail order that any, or many, could have been responsible for the disease.

importations of Japanese chestnuts are well documented; the earliest may have been in 1876 by nurseryman S. B. Parsons of Flushing, New York. But, there were so many records of these trees being imported and shipped through mail order that any, or many, could have been responsible for the disease.

The first person to take note of the blight was Herman W. Merkel, a Forester working at the Bronx Zoo in 1904 who had examined some orange spotting on the chestnuts growing on the zoo grounds. In a 1905 report, Merkel wrote “…a few scattered cases which occurred [on American chestnut trees] during the summer of 1904. Early last June [1905] this disease was noticed on so many widely scattered trees of all sizes that specimen branches and an appeal for information were sent to the USDA“.

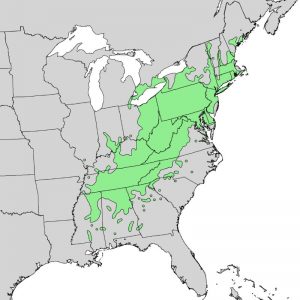

By 1909, the blight had been reported in Akron, Ohio. It was spreading at least 50 miles a year. By the 1930s, the disease had spread to over 200,000,000 acres nearly every stand of chestnut tree in the eastern United States was dying.

Don’t It Always Seem To Go?

Technically, the American chestnut is not extinct, nor in danger of becoming so. The pathogen that afflicts the tree only destroys the above ground tissues, while the roots are left intact. And any sprouts produced, eventually succumb to the omnipresent death spores. The eastern woods still have chestnut stumps covered with diseased, shrubby branches.

Thanks to science, solution may not be too far away. The fungal pathogen that causes Chestnut blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, has long been identified and scientists are seeking a cure on a variety of fronts.

Thanks to science, solution may not be too far away. The fungal pathogen that causes Chestnut blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, has long been identified and scientists are seeking a cure on a variety of fronts.

One promising effort involves a gene modification experiment to create transgenic blight-resistant chestnut trees.

Another team of scientists are working on the development of a biological control fungicide to attack C. parasitica.

Scientists from State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry is working on the creation of a hybrid tree that is 15/16th American Chestnut and 1/16th Oriental Chestnut. Their project is examined here: “Can We Engineer an American Chestnut Revival?”

While there are perhaps fewer 100 mature trees alive within the historic range of the American chestnut, healthy stands can be found out of the range of the pathogen. The world’s largest surviving stand of American chestnuts grows on private land in West Salem, Wisconsin, where over 1000 trees are growing on 60 acres. The trees are offspring of 8-10 trees that had been planted in the 19th century by an early settler named Martin Hicks.

Closer to home, there are 5 experimental American chestnut trees growing on the east side of the former estate of salt magnate Joy Morton in Lisle, Illinois.

Today, the only chestnut trees in the Fox River Valley are horse chestnuts, which aren’t true chestnuts. The only chestnuts we roast over open fires these days are imported from Italy and called Spanish chestnuts.

The song will be played and sung hundreds of times in the coming weeks and people will smile. The sad saga of the American chestnut never did affect the tune’s popularity. In 2004, The Christmas Song was voted the most-loved seasonal song with women aged 30–49.