By Gary Mechanic, Executive Director

Late last year one of the final pages of a decades long battle to save Long Lake (in Lake County Illinois) came to a close when Illinois’ Attorney General Lisa Madigan announced a settlement with Baxter Healthcare that will end that company’s decades-long pollution of Long Lake. Behind the Attorney General’s suit against a 17 billion dollar multinational corporation, that’s based in Illinois, stands Paige Fitton, Paige’s childhood friend Jennifer, Paige’s mom and dad, and Paige’s grandfather and great-grandfather! It took generations of lake lovers, homeowners and Paige’s family working together for decades to reverse decades of degradation and win a complicated war against a powerful polluter.

This is the second of a three-part series describing that decades long, multi-generational, battle to save Long Lake from a long, slow death by pollution. Read Part One Here

Killing Long Lake

James W. Cooper and his young wife Helen found their newly built cottage on the shore of Long Lake the ideal place to escape from the summer heat of Chicago, enjoy the lake life and introduce their young son to the beauty of the natural world.

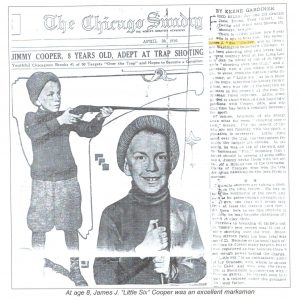

Their son, James Johnson Cooper, was born in 1907. Better known to all around the lake as “Jimmy”, he grew from a toddler into a strong young boater, fisherman, and marksman as he spent his long childhood summers at the lake cottage. “Little Six” as he was known at the Long Lake Gun Club, won fame in 1916 when, at the age of eight, he shot 41 out of 50 targets in a trap shooting contest. He would grow into a husband, father and the grandfather of Paige Fitton. The cottage his father built in 1906 wouldn’t be connected to a public sewer system until the mid-1970’s. By the time James J. died in 1979, his beloved Long Lake was nearly dead.

Their son, James Johnson Cooper, was born in 1907. Better known to all around the lake as “Jimmy”, he grew from a toddler into a strong young boater, fisherman, and marksman as he spent his long childhood summers at the lake cottage. “Little Six” as he was known at the Long Lake Gun Club, won fame in 1916 when, at the age of eight, he shot 41 out of 50 targets in a trap shooting contest. He would grow into a husband, father and the grandfather of Paige Fitton. The cottage his father built in 1906 wouldn’t be connected to a public sewer system until the mid-1970’s. By the time James J. died in 1979, his beloved Long Lake was nearly dead.

Dirty Water

The First World War interrupted the idyllic summers for most Long Lake families. But with the end of the western world’s struggle,  development resumed around the lake. As more and more summer cottages began sprouting up around its shore, they added the waste water contributions of the full time and occasional residents to the high water table of the wet lands into which their septic systems were installed. To where do you suppose the waste of this cottage (shown here in 1913) built on the shore of the lake, ultimately drained?

development resumed around the lake. As more and more summer cottages began sprouting up around its shore, they added the waste water contributions of the full time and occasional residents to the high water table of the wet lands into which their septic systems were installed. To where do you suppose the waste of this cottage (shown here in 1913) built on the shore of the lake, ultimately drained?

As the demand for farmland within reasonable transport distance of Chicago increased, the miles of farm drain tiles laid in the Squaw Creek and Long Lake watersheds increased exponentially. The wet lands of Lake County required far more extensive draining to be tillable than the well-drained moraines and prairies to the west and south. The miles of tiles, and hundreds of septic systems began incrementally increasing the pollution load entering Long Lake.

Fast Times on Long Lake

As the Cooper’s Long Lake neighbors who had learned mechanics in World War I, began returning from the war to summer boating on the lake, they began dropping surplus aircraft engines into speedboats and racing them on the Chain.

As the Cooper’s Long Lake neighbors who had learned mechanics in World War I, began returning from the war to summer boating on the lake, they began dropping surplus aircraft engines into speedboats and racing them on the Chain.

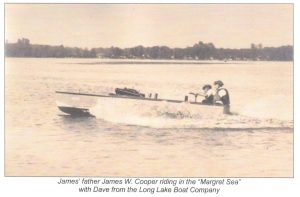

When Jimmy Cooper graduated from high school in 1923, he was given an aircraft motor. When it was installed in a speedboat call the Margret Sea, and local boat builder Dave, from the Long Lake Boat Company hit the throttle, Jimmy’s father James nearly swallowed his cigar!

Dam!

By the 1930’s the population of the Long Lake area (Grant Township) had reached 1,650 and Lake County was home to more than 100,000.

On top of the pressure of population, development, farm tiles and failing septics, the home owners around Long Lake found another way to add to the lake’s woes.

Sometime in 1930, a Long Lake resident, with access to large motorized earth-moving equipment, decided it would be an improvement on nature to cut a channel across the ridge separating Long Lake from the Chain of Lakes. After all, hadn’t the mighty economic engine of Chicago itself roared to life with the creation of a canal cutting across a watershed divide?

Surely expanding the recreational opportunities from little (336 acres) Long Lake to the huge expanse of the Chain would not only expand recreation, but would instantly increase the value of each lakeside owner’s property!

Without a survey, much less a permit, a channel was cut between the wetland headwaters of Squaw Creek and the wetland marshes on the south side of Fox Lake, thereby extending Squaw Creek all the way into Fox Lake, connecting it with the Fox River. When the last barrier between the lakes was dredged, the rush of water that began draining out of Long Lake alarmed the residents. It was quickly discovered that Long Lake was several feet higher than the level of Fox Lake!

Something had to be done and done quickly. The Long Lake Improvement and Sanitation Association sprang into action and built a  temporary barrier, and then a dam with a boat lift across Squaw Creek. The lake was saved from being surrounded by huge new mudflats. And the boaters, with some effort, could still access the Chain.

temporary barrier, and then a dam with a boat lift across Squaw Creek. The lake was saved from being surrounded by huge new mudflats. And the boaters, with some effort, could still access the Chain.

No one thought about the biological consequences of connecting this ancient glacial lake, that had evolved a balanced aquatic ecosystem in isolation over the last 4,500 years, with the Fox River system which flows through Fox Lake, or how it would change Long Lake forever.

To this day, the Long Lake Improvement and Sanitation Association maintains the Long Lake dam, hoist, and sluice gate. Their website states:

“The dam allows us to keep Long Lake’s water level two feet higher than what it would otherwise be. Much of the lake would become beachfront without the dam, severely affecting property values and recreational opportunities. The hoist provides a means to bypass the dam, allowing access between Long Lake and the rest of the Chain o’ Lakes. The sluice gate allows us to evacuate water from Long Lake during periods of high water and flooding, such as we experienced in April 2013.”

Look at Google Maps or Google Earth and see if you can find the boat lift and dam on Squaw Creek.

Making Long Lake a Sewer

Beginning in the 1950’s the nearby Round Lake Sewage Treatment Plant, and the Lake Villa Sewage Treatment Plant hastened the death of Long Lake. The daily effluent from these plants dumped tons of nutrients into their “receiving streams” that led to Long Lake. Over-fertilization of the water led to the eutrophication of the lake. The lake changed from one with dense aquatic plant stands and clear water, to a muddy lake with few aquatic plants and increased algae blooms. Fish kills were first reported in 1950’s, including a severe kill in 1958. When the lake was surveyed in 1967, the lake was quite turbid and carp dominated the fishery.

In 1975 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency surveyed Long Lake and concluded that the lake was eutrophic (it ranked 29 out of 31 Illinois lakes), and that point sources contributed most of the phosphorus in the lake. This study found that the Round Lake Sewage Treatment Plant contributed 82% of the total phosphorus (TP) or 44,000 pounds per year at 2.2 MGD (million gallons a day) and the Lake Villa Sewage Treatment Plant contributed 2.5% of the TP or 1,323 pounds per year at 0.3 MGD.

Non-point source pollution entering Long Lake was estimated in 1975 at 6,800 pounds of TP per year. A total of 53,736 pounds of TP per year from all sources entered Long Lake of which an estimated 63% remained in the lake.

Non-point source pollution entering Long Lake was estimated in 1975 at 6,800 pounds of TP per year. A total of 53,736 pounds of TP per year from all sources entered Long Lake of which an estimated 63% remained in the lake.

Another more intensive survey by the Illinois EPA in 1979 concluded that Long Lake was turbid, had high algal production (mostly Aphanizomenon), and classified the lake as in poor condition. This report also stated that the major source of phosphorus and nitrogen was from the Round Lake Sewage Treatment Plant.

But Wait, It Gets Worse!

In 1964 the Baxter Healthcare Corporation built the first building of its Round Lake Research and Development Facility near Squaw Creek at the intersection of Rt. 120 and Wilson Road. The R&D center grew to more than a half dozen large buildings (with larger parking lots), and would at one point employ about 2,000 people. Of course all that storm and wastewater had to go somewhere. So Baxter started discharging its treated industrial wastewater into the creek. Two and a half miles downstream Squaw Creek discharges into Long Lake.

Although the Long Lake residents began connecting to local sewer systems in the late 1970’s, reducing the pollutant load from failing septic systems, and the Lake Villa and Round Lake Sanitary Districts stopped sending their wastewater into the lake in the 1980’s, county, state and federal agency studies reported that water quality in the lake continued to get worse.

When Baxter HealthCare’s permit to discharge into Squaw Creek was up for renewal in 2001, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency held a public comment meeting in Round Lake. Residents asked Baxter to stop discharging their treated sewerage into Squaw Creek and Long Lake.

Fake News is Nothing New

As a result of residents’ objections, the Long Lake Improvement and Sanitation Association met for several months with Baxter  representatives. Baxter told the LLISA representatives that “due to the location of the public sanitary sewers in the region and the capital outlay required, alternative options should be considered.” In other words, it would cost Baxter too much to hook up to the public sewer.

representatives. Baxter told the LLISA representatives that “due to the location of the public sanitary sewers in the region and the capital outlay required, alternative options should be considered.” In other words, it would cost Baxter too much to hook up to the public sewer.

What Baxter didn’t say was that it had contacted both nearby wastewater treatment facilities. Both were reluctant to accept Baxter’s waste without requiring large fees to enable them to upgrade their facilities to properly treat industrial waste.

Instead, Baxter announced they would use their treated wastewater to irrigate an adjacent nursery, and during winter months the water would be retained in a storage pond. They issued a press release and applied for a land application permit from the IEPA, which was issued.

However, Baxter never carried out this plan. For the next 16 years, little Squaw Creek silently accepted Baxter’s treated industrial wastewater averaging more than 250,000 gallons per day – the equivalent of 625+ homes discharging into Long Lake. It took the 4th generation of the Cooper family to discover Baxter’s duplicity and begin saving Long Lake.

Next Month: Saving Long Lake