By Gary Swick, FOFR President

I have been asking folks for decades, “What is a watershed?” It is important to us because Friends of the Fox River  (FOFR) is Creating a Watershed of Caretakers. Understanding the term/concept is essential in maintaining and protecting our Fox River.

(FOFR) is Creating a Watershed of Caretakers. Understanding the term/concept is essential in maintaining and protecting our Fox River.

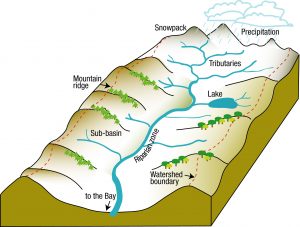

A watershed is not a building where the well is or water is stored. A watershed is a drainage system: an area of land where all of the water from above, below, and draining across collects in the same place (e.g., The Fox River). Very simply, visualize a funnel; no matter where water enters it, it ends up in the same place.

Gravity Rules!

A watershed has physical boundaries and influences. Picture a house with a peaked roof: if rain lands on a south facing slope it will drain down the home’s south side, rain on the north slope flows down the north side. The roof’s peak is the drainage area boundary and the physical forces in play are elevation and gravity. Unless humans intervene, water follows the path of least resistance.

Building a Watershed

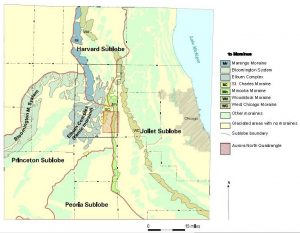

The Fox River’s watershed was formed by glaciers (a mile thick in some places) that carved out the previous landscape as they slowly moved and left behind hills and valleys. As the glacial ice melted, it created the current landscape. Where huge chunks of ice broke off and melted more slowly, they created depressions that became lakes, and as the glacial torrents ran out, their weight flattened the landscape (e.g., central Illinois). When the finely ground rock material (loess) was carried by wind it created the foundation for some of the most fertile soil in the world. The glacial action created small drainages (sub- watersheds). The drainages combined, like puzzle pieces, to make the whole Fox River Watershed.

The Fox River’s watershed was formed by glaciers (a mile thick in some places) that carved out the previous landscape as they slowly moved and left behind hills and valleys. As the glacial ice melted, it created the current landscape. Where huge chunks of ice broke off and melted more slowly, they created depressions that became lakes, and as the glacial torrents ran out, their weight flattened the landscape (e.g., central Illinois). When the finely ground rock material (loess) was carried by wind it created the foundation for some of the most fertile soil in the world. The glacial action created small drainages (sub- watersheds). The drainages combined, like puzzle pieces, to make the whole Fox River Watershed.

Watersheds Connect Us

The United States Environmental Protection Agency has mandated that the Fox River watershed communities take  action to improve oxygen levels in the Gulf of Mexico. Excess nutrients which enter in the Stoney Creek watershed can flow into Otter Creek, continue into Ferson Creek (all west of the Fox River between the Elgin and St. Charles dams), then into the Fox River.

action to improve oxygen levels in the Gulf of Mexico. Excess nutrients which enter in the Stoney Creek watershed can flow into Otter Creek, continue into Ferson Creek (all west of the Fox River between the Elgin and St. Charles dams), then into the Fox River.

Excess nutrients from one place can contribute to low oxygen levels in another. But the water does not end its journey there. The Fox River joins the Illinois River and eventually becomes part of the Mississippi River watershed which ends in the Gulf of Mexico. To manage a river’s health is to manage its entire watershed. We all live downstream.

A Meter of Moisture

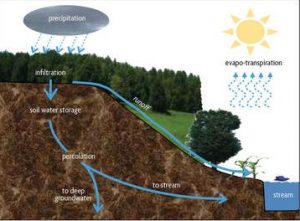

The formation of a watershed is only the beginning of this important lesson. In Northern Illinois, we usually enjoy thirty-nine inches (one meter) of annual precipitation, which is mostly rain and snow. Before humans settled here permanently, the equivalent of only four inches of that precipitation would run off the land into surface-water features like a lake or stream, and the other thirty-five inches would infiltrate the ground. Twenty-seven inches of the infiltrated water would be absorbed by plant roots and used in photosynthesis or released into the atmosphere in the process of transpiration. The remaining eight inches would be soil-bound as groundwater. In much of the Fox River watershed, many streams including the Fox River, actually begin as groundwater and are forced to the surface as springs, by hydrological pressure.

The formation of a watershed is only the beginning of this important lesson. In Northern Illinois, we usually enjoy thirty-nine inches (one meter) of annual precipitation, which is mostly rain and snow. Before humans settled here permanently, the equivalent of only four inches of that precipitation would run off the land into surface-water features like a lake or stream, and the other thirty-five inches would infiltrate the ground. Twenty-seven inches of the infiltrated water would be absorbed by plant roots and used in photosynthesis or released into the atmosphere in the process of transpiration. The remaining eight inches would be soil-bound as groundwater. In much of the Fox River watershed, many streams including the Fox River, actually begin as groundwater and are forced to the surface as springs, by hydrological pressure.

Dismantling a Watershed

Human settlement changed the landscape significantly and started on the path of degrading habitat and water quality. Clearing the land of forests and prairies disrupted the role of plants in the water cycle. Draining wetlands for agriculture and channelizing streams for irrigation did further damage. Then came the conversion of pervious (porous, where water can infiltrate the ground) surfaces into impervious surfaces like roof tops, sidewalks, streets, parking lots, and even many lawns. This changed the watershed’s integrity because impervious surfaces greatly reduced infiltration and plant absorption. Water that would normally go in the ground, either evaporates or ends up in the river.

Too Much and Not Enough

The natural drainage system has undergone significant physical alterations. Increased runoff has caused habitat loss through soil erosion. In the Tyler Creek watershed west of Elgin, high water flow is now four times what it was in the 1980’s. As the climate changes, record rainfalls and the resulting flooding events are increasing. An additional contributor to flooding is the increase in impervious surfaces (e.g., parking lots). What formerly was absorbed now becomes runoff. Additionally, we are extracting drinking water from the groundwater system much faster than it is being replenished, and adding it to the river. We are forced to manage both quality and quantity issues within our watershed. Groundwater is now a finite resource.

Sanitary Sewer vs Storm Sewer

Much of Elgin’s and Aurora’s drinking water comes from the Fox River. The other municipalities in the watershed extract groundwater for residential, commercial and industrial use. After we are done using water it is flushed or drained via a sanitary sewer to a wastewater treatment facility. The process of mining water out of the ground and depositing it in the river is steadily increasing the quantity of the Fox River and its flow rates. At one time, water running off streets after a storm and residential wastewater were combined for treatment. When quantities were overwhelming the treatment facilities, local towns separated the two sewer systems. So now whatever goes down a street’s drain goes untreated to a tributary and eventually to the Fox River.

Much of Elgin’s and Aurora’s drinking water comes from the Fox River. The other municipalities in the watershed extract groundwater for residential, commercial and industrial use. After we are done using water it is flushed or drained via a sanitary sewer to a wastewater treatment facility. The process of mining water out of the ground and depositing it in the river is steadily increasing the quantity of the Fox River and its flow rates. At one time, water running off streets after a storm and residential wastewater were combined for treatment. When quantities were overwhelming the treatment facilities, local towns separated the two sewer systems. So now whatever goes down a street’s drain goes untreated to a tributary and eventually to the Fox River.

The Enviroscape

Street drains (storm sewers) receive winter salt, lawn chemicals, automotive leakage, grass clippings, pet waste and other illicit stuff, like litter. Considering this, it is incredible that we still have healthy streams and rivers. Friends of the Fox River uses a watershed model, the Enviroscape, to demonstrate the process of how what we do on land affects the river, in classrooms and at events. When people see this demonstration, it is clear to them how a watershed works and how humans can negatively impact the watershed.

What is a Watchdog?

The term watershed is not the only troublesome term for me to explain. One day, I was preparing a group of 5th grade students for their experience of collecting data in their local stream, Stoney Creek. I referred to their role as being “Watershed Watchdogs.” As a teacher I am familiar with blank looks of confusion and these students were politely lost. I inquired about their knowledge of watchdogs and found none of them had ever heard of a watchdog. So, I replaced watchdog with security guard; one who looks for abnormal conditions, investigates, and takes action, which often is to notify a higher authority. Then they understood my point.

Creating a Watershed of Caretakers

The next part of the story is about how we “Keep on Fixin’ the Fox” through advocacy, restoration, and education. We are creating a watershed of caretakers. It begins with awareness of our watershed and understanding of how we impact it. Then it moves to how do we do better as caretakers. That will be the July chapter.